Since publishing my first book in 2010, much has happened including newly-found Irish relations, more discoveries about my colorful Irish ancestral family, serendipitous crossing of paths with people who have a connection to my family story and more experiences that affirm my belief about the inherent goodness of people……even strangers. This Post-Scripts blog will allow me to share these post-publication discoveries and experiences with you as well as being a place where I can tell you more surprising and interesting true stories of the past in Jersey and share my genealogical tips and experiences. Please pass on the link to this page and encourage others to stop by. There is so much more that connects us than divides us……if we just look. Maureen

**********************************************************************************

Enjoy a video of Maureen reading two of the stories from her book Jersey! Then . . . Again:

New Jersey Suffragettes – The Quest for Votes for Women

Oliver Phelps Brown – 19th Century Medical Quack & Con Man

***********************************************************************************

December, 2013

NJ350 – New Jersey’s 350th Anniversary Celebration – 2014:

Innovation, Diversity, Liberty

Immigrants in New Jersey: Oscar Schmidt – Music-Maker

My penchant for “old things” has found me trolling through rows of tables at outdoor flea markets on many an early morning hoping to discover antique treasures. Over the years, scanning those tables searching for something wonderful and scoring it at a bargain price meant a lot of talking with sellers and dealers. Those conversations, whether or not they led to a deal being struck and a purchase being made, were a real opportunity to learn from people who had amassed a great deal of information and expertise about the things they specialized in buying, collecting, and selling. That casually-acquired knowledge can come in handy . . . as it did when I was in writing this story. How else would I have known what a “zither” is?

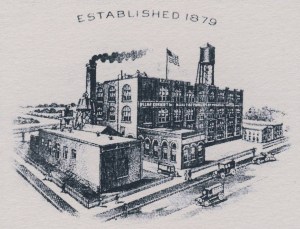

A zither is a stringed instrument dating to before the birth of Christ. Sometimes mistakenly referred to as an autoharp (a similar but distinct instrument), a zither may be played laid on a flat surface or propped in the player’s lap and may have as few as a dozen strings or as many as 50, depending on the specific type. Zithers enjoyed a wave of popularity in the late 1800s and early 1900s and were found in many homes where they were used for parlor entertainment. A premier maker of zithers at that time was Oscar Schmidt, a German-born immigrant who formed a music publishing company in New Jersey in about 1879.

Schmidt, an astute businessman and entrepreneur, expanded his music publishing firm, opening a chain of music schools and using those schools to promote sheet music sales. He soon realized that he could then leverage his music school business by supplying instruments to the students. By the late 1890s, Schmidt was manufacturing zithers, mandolins, banjos and guitars at a large 30,000 square foot factory he opened on Ferry Street in Jersey City.

In the early years of the 20th century, the Oscar Schmidt Company was among the largest manufacturers of stringed instruments with over a million instruments reportedly produced at the Jersey City factory and instrument sales around the world.

In addition to his success in the music business, Schmidt was an active investor in real estate. Among his property purchases, in 1900, was a large parcel and house on Palisade Avenue in what was then known as Hudson City. Extensive renovations were commenced by Schmidt, including raising a third story on the existing house, adding multiple bay windows, extending the dining room, and installing the latest in modern conveniences, including steam heat, electric lights, “ornamental fixtures and first-class bathrooms.” The property was to have terraced landscaping with trees, flower beds and gravel walks and driveways. The cost of the work was expected to be at least $12-14,000.

There is no doubt that Oscar Schmidt, his wife and children were living very well as the result of Schmidt’s hard work and business acumen but newspapers of the day did occasionally capture them dealing with life’s ups and downs. In 1905, Mrs. Schmidt, accompanied by her daughter, drove out in their horse carriage with Mrs. Schmidt at the reins. Crossing Booream Avenue, the carriage was hit by a trolley. Mrs. Schmidt, who maintained that the motorman had not given any warning of the approaching trolley, somehow kept her head and control of the careening, damaged horse carriage, subduing the terrified horse and bringing the carriage to a stop. Cut and bruised, she was credited for her “skill and presence of mind” that prevented a much worse calamity.

Two years later, the Schmidts were involved in another vehicle-related incident when a horse and wagon belonging to Oscar went missing after being driven from Jersey City to New York by an employee, Louis Droove, who had taken a boy “helper” with him. When neither Droove or the boy – or the company horse and wagon – returned by the late evening, the police were notified. The following morning, the boy reappeared, telling the police that at 2am the previous night Droove had dropped him off on Barclay Street in New York saying that he should “beat it for the ferry and run home.” The boy was unable to explain where they had been all day and night except to say that frequent stops were made at saloons. Some hours later, Jersey City Police were contacted by the 57th Precinct in Brooklyn saying they had found a “driverless horse and wagon bearing the name of Oscar Schmidt of Jersey City Heights.” Droove, however, remained among the missing.

Oscar Schmidt died in 1929 while visiting one of his overseas factories, a month before the stock market crash and onset of the Great Depression, those events severely weakening the company which ultimately did not survive. Nonetheless, the Schmidt name and branding has lived on under the ownership of other instrument manufacturers to this day.

Oscar Schmidt came to New Jersey to pursue liberty and opportunities. Like so many immigrants before and after him, he brought his native culture and enterprising spirit to his new home, contributing to the diverse story of our state and America.

**********************************************************************************************************

September, 2012

Maureen featured in the Daily Record newspaper:

Genealogist shares tools to trace your Irish roots

PEQUANNOCK — Genealogist Maureen Wlodarczyk of Sayreville held an audience spellbound at the Pequannock Township Public Library recently as she shared stories from the lives of her Irish ancestors — and the tools she used to unearth them.

In Morris County, genealogical attention is well focused on Ireland. According to 2010 U.S. Census statistics, 21 percent of the population here claims some Irish ancestry. The county is also home to the Irish American Association of Northwest Jersey, the Ancient Order of Hibernians and other Irish groups.

Wlodarczyk, whose great-great-great grandparents were potato famine immigrants, has lots to tell in her book, “Past-Forward: A three-decade and three-thousand-mile journey home” (Outskirts Press, $26.95).

Written in the form of a letter to her beloved grandmother, Kate, the book traces, among other narratives, the fate of Kate’s maternal Irish ancestors. Like many families, they emigrated from Ireland to Jersey City and, eventually, moved to other suburbs throughout New Jersey.

Wlodarczyk, a self-described “unrepentant history addict,” knew to start her search in Ireland’s County Mayo and County Sligo by using a Surname Map of Ireland.

“Irish names are often rooted in locales,” she said.

Using ship and Census records and the New Jersey State Archives, she traced arrival, birth, marriage, and death dates, as well as occupations.

In 1862, Delia Hough, then 13, ventured from Ireland alone. She was passenger No. 400 in steerage on the Vanguard, a ship headed to the United States, where she would be self-supporting as a housemaid until she married John Flannelly, who was injured fighting in the American Civil War during the Battle of Williamsburg.

Delia’s daughter, Mamie Flannelly, was “an ironer in a laundry” whose first child, a son, was born out of wedlock. It was at GenealogyBank.com, a database of stories from American newspapers dating to 1690, that Wlodarczyk pieced together Mamie’s likely story.

“One account said Miss Mamie Flannelly led the opening march with Mr. John Nagle, president of the employees association,” Wlodarczyk said. “I picture her in a secondhand dress, with that red hair, thinking how that was the best night of her life. It was Mr. Nagle who fathered her child.”

Then he abandoned her. Wlodarczyk said she couldn’t stop thinking about how, almost eight months later, the pride Mamie felt at the dance would have been transformed to shame in the eyes of her co-workers. It was her own “scarlet letter.”

Two years later, Mamie married Patrick Joseph Whalen, a ne’er-do-well alcoholic, according to Wlodarczyk. The couple had four children before Mamie died at age 35. Whalen gave up his children, one of whom was Wlodarczyk’s grandmother, Kate.

That’s where Wlodarczyk employed one of her key research tools — the notebook she’d used in the 1970s to write down her grandmother’s sparse replies to questions about her family.

“She always said she’d rather not air her dirty linen in public,” said Wlodarczyk, who was in her 20s when she did those interviews.

But the author embraces her whole genealogy, warts and all.

“You have to understand we’re not all descended from Queen Elizabeth. It’s even money you’ll find out something that surprises or disappoints you,” Wlodarczyk said. “We have to remember that they were saints and sinners. They were just like the rest of us. They persevered. They did what they had to do. They made decisions. Some of them weren’t the best, but we weren’t there, so we can’t say.”

It came to be that Kate was employed as a maid at age 13 after her mother, Mamie, died.

“Would Delia have felt sad that her granddaughter was starting out her teenage years in the same predicament she’d endured?” Wlodarczyk wondered aloud. That was one of many questions she pondered even as her research continued.

Indeed, she tracked down the house where her grandmother worked as a servant for the Esterbrook family in Jersey City. Its current owner gave Wlodarczyk a tour of the home, which was intact, though much changed. While walking through the home, Wlodarczyk was struck with the thought that her grandmother Kate would have touched the thick, old oak doors that were still there.

“I put the flat of my hand on a door, which I feel certain she probably touched many, many years earlier,” she said.

The moment was one of several in which all the years of research — collecting nugget upon nugget of information —made her lineage come alive for her. Along the way, Wlodarczyk has found new family and friends. At one of her talks, she told those assembled at the Pequannock library, a member of the Esterbrook family was in the audience and asked if her family had treated Kate well.

“We were excited to host Maureen’s program because there are so many library patrons who are passionate about genealogy,” said Rose Garwood, library director.

Among them was Jennifer Boggess of Massachusetts, visiting her hometown of Pequannock and looking to Wlodarczyk for good questions to ask her 90-something grandmother. Remembering all she wished she’d asked her grandmother Kate in the ’70s, Wlodarczyk gave Boggess an interview questionnaire she now shares with people just beginning to research their family stories.

It is one of many ways Wlodarczyk informs and guides people.

Today, she said, people still ask her if she’s embarrassed to say that her great-grandmother had a child out of wedlock and that her great-grandfather was an alcoholic. She is not. Indeed that knowledge makes Wlodarczyk all the more admiring that her beloved Kate was such a profoundly beautiful mother and grandmother.

The journey took Wlodarczyk 30 years, including a couple of trips to Ireland to feel even more deeply the fabric of those lives that yielded hers. She researched as time and finances allowed. As busy as life is, she said, she wouldn’t have missed the journey for all the world.

Written by: Lorraine Ash – The Daily Record

**********************************************************************************

February 2012

Genealogy buffs, it’s that time again: Who Do You Think You Are? will begin its new (and longer) season on NBC on Friday, February 3 at 8pm. I was recently interviewed by SheKnows.com about involving children in genealogy using family trees and other activities. Read the piece at: http://www.sheknows.com/parenting/articles/852083/teaching-kids-history-through-a-family-tree

*****************************************************************************************************

December 2011

The Authors Show Interview – Take a Listen:

http://www.walterwlodarczyk.com/misc/maureen-wlodarczyk-author-show.mp3

*********************************************************************************************

November 2011

One Thing Leads to Another – Redux

As readers of this blog, family and friends know, I cannot resist a genealogical challenge and helping others achieve a breakthrough in their family history research is pure nirvana for me. I had one of those adrenalin-pumping ancestor chases this past week – the kind that are unexpected, dripping with detective drama and a side of serendipity and proving, yet again, that in genealogy, one thing leads to another.

Just about a year ago, I reconnected with a high school friend. We had both been on the twirling squad in school and stayed in touch for a number of years post-marriage and children. Then, for no reason I can really pinpoint, we drifted in different directions and lost track of each other. Reconnecting and catching up on decades (yes, decades), we realized, more than we ever had, how much we have in common. Although we had dissimilar work lives and have different religious views, for example, there is an undeniable synchronicity between us. We discovered that we were born two weeks apart in the same hospital, that we both spent the earliest years of our childhoods in Jersey City and that my maternal grandparents and her paternal grandparents attended the same church there, as did her father and my mother. And . . . wait for it . . . we also discovered that, like us, our mothers graduated from the same high school (albeit a few years apart). Each of us had a much closer bond with our mother than our father (for a good reason in each case). And then there’s the wardrobe thing. The first two times we met, we turned up wearing “matching” outfits, as if we had planned it the way girlfriends sometimes do when they are ten years old. When I say matching, I mean it – right down to a black and cream hounds-tooth jacket, red top and black slacks. Freakish.

As we emailed back and forth telling each other what we had been up to during our years of separation and attaching photos for illustration, I told her about my years of genealogical searching that gave birth to two books and a second “career” speaking and writing about my favorite addictions: genealogy and local history. She was interested in doing some family history research about her husband’s family and her own. Sniffing the scent of a new challenge, I was more than happy to offer my help. A lot of revelations have resulted and, as is almost always the case, some were happy or surprising in a good way and others were sad or unpleasant.I suggested some months ago that we make a field trip to the NJ State Archives, a top spot for doing family research. The Archives is a treasure trove of information about births, deaths and marriages in NJ, particularly covering the period from 1848 through the early decades of the 1900s. The Archives staff, professional and very knowledgeable, are themselves a great resource for researchers. We finally got to the Archives about two weeks ago. I had recommended (more like “instructed”) that my friend review the information I had already uncovered (census lists, etc) and prepare a list of the records she wanted to look for so we could have a clear focus for the searching. She did.

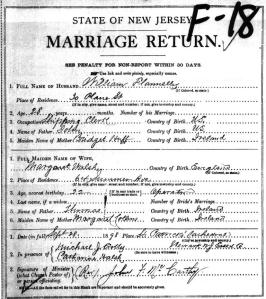

I gave her a quick overview of how the records and films were organized, how the microfilm reader worked, and the basic rules (yes, you have to leave your purse, water and food in the provided locker, no pens – just pencils allowed, etc). I encouraged her to ask the archivists for help when she got a bit turned around or couldn’t find what should have been on a particular roll of microfilm. That strategy paid off and very quickly. My friend already had a marriage record that included the maiden name of her great-great-grandmother but we couldn’t make it out with any certainty. The archivist suggested looking for a marriage or birth record for another sibling in the hope of hitting upon an easier to read surname. The search for that, however, turned up another record with an equally undecipherable name. The archivist then switched gears and suggested looking for delayed birth record filings which, frankly, seemed like a real long-shot. Well, it was actually a bulls-eye as a typed 1949 (much) delayed birth filing was found and there was that elusive surname, plainly legible. More records were found during our three-hour Archives visit and a look at the list we started with confirmed that the most important of the items had been found. In and of itself, this constituted a great first attempt and a very successful day but, in fact, it would also turn out to be the “one thing” that would quickly lead to another . . . and another.

My friend had been told that her family was part “Dutch.” Not Pennsylvania “Dutch” (who were really “Deutsch” meaning German) but windmills, tulips and wooden shoes Dutch. Was that ever true! A couple days after our Archives visit, I went on Ancestry.com and started searching on the newly-revealed maiden surname of my friend’s great-great-grandmother. I was able to find an 1870 US census record with the last name misspelled but clearly the correct family. That census record led me to public family tree postings and the surprising discovery that the last name had been anglicized (either by the family or the census taker) and to a tree that included the proper Dutch spelling of the surname. I couldn’t wait to search on that name and without much delay that led me to the ship passenger record for my friend’s great-great-great-grandparents who had traveled to America from Rotterdam, Holland in the mid-1850s. Traveling with them was a baby daughter listed as having died during the trip across the Atlantic and a son who survived the voyage. Another example of how genealogical research delivers both the happy and sad news that can still touch our hearts so many generations later and informed our ancestors’ lives, struggles and triumphs.

The family tree that put me on to the original Dutch family name included two additional generations of my friend’s family, thus taking us back to fifth great-grandparents and the late 1700s in a tiny town in Holland. I excitedly called my friend to tell her what I had found. I caught her on her cell phone in the aisle at Toys ‘R’ Us shopping for a birthday gift for her little grandson. All shopping activity stopped as I gushingly told her the story. I asked her if she wanted me to contact the owner of the family tree (through Ancestry’s blind messaging function) to tell them about her and ask if they wanted to contact her. For a moment I thought she might say no, but she didn’t. I have since sent the message through Ancestry. No response as yet but, with the luck we have been having, I wouldn’t be surprised to hear from her newly-found relatives. My friend, who likes to use clever pseudonyms when emailing me (for example “Dear Sherlock”), signed a recent email “Double Dutch Girl.” Indeed.

*********************************************************************************************

October 2011

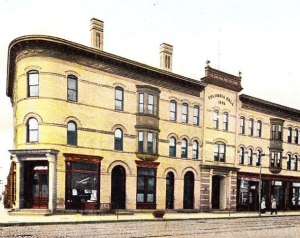

Charles Dickens and the Hudson County Jail

Part One:

Old Charlie Dickens is one of my favorite authors. A Christmas Carol, A Tale of Two Cities and Little Dorrit – I love them all. Who doesn’t know who Ebenezer Scrooge and Tiny Tim are? Who doesn’t remember lines like: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times . . .” and “It’s a far, far better thing that I do, than I have ever done . . ?” Little Dorrit is a lesser known part of Dickens’ body of work but, with one of its central events being a greed-fed financial collapse at the hands of a ponzi-schemer, it is as timely today as it was 150 years ago. (Not to mention that Charles Ponzi, the swindler who gave pyramid schemes their name, was not born until some 25 years after Dickens first published Little Dorrit.)

So, what does Dickens have to do with the Hudson County Jail? Well, the title Little Dorrit refers to one Amy Dorrit, born in an English debtor prison where her father, William Dorrit, was an inmate. In Merry Olde England, it was not unusual for wives and children of imprisoned debtors to join them in prison. Amy’s father, once a “gentleman,” had a precipitous fall from grace due to the unscrupulousness of others and wound up a destitute inmate of the Marshalsea Prison in London. Charles Dickens was very familiar with the Marshalsea Prison. His own father had served time there in the 1840s for failing to pay a debt. Dickens drew upon his personal experiences in crafting the characters in Little Dorritt and telling the tale of William Dorrit’s fall and imprisonment, his years-later rise and restoration back to the status of “gentleman” and his second fall as a victim of the ponzi scheme.

In Little Dorrit, William Dorrit, during his many years as an inmate, becomes known as the “Father of the Marshalsea,” a dean of sorts in the prison community. In that regard, he is treated with some amount of deference by his fellow prisoners and even by the jailers of the prison and he clings to that small measure of respect as evidence that he is still a “gentleman.”

In doing some research recently, I happened upon a story about a similarly “senior” prisoner who, for many years in the second half of the 1800s was known as the “star boarder” of the Hudson County Jail. No, he was not a lifer nor did he serve a long-term sentence. He was just a “regular.” In and out of the Hudson County Jail (more in than out) over a thirty-year period, often unable to care for himself or homeless, he deliberately got himself committed to jail.

This star boarder was named Charles Middleton and came from a prosperous New York family. Why he was estranged from them I couldn’t find out but, from newspaper pieces I found, it appears his family tried to help him without success. Charles Middleton was better known by the moniker “Baldy Sours.” How he got that name I don’t know, but Jersey City locals all knew him by that name, as did the local newspaper, the Evening Journal.

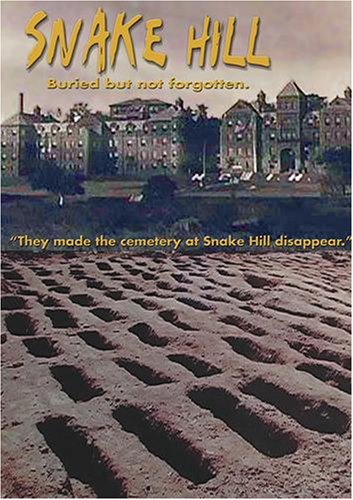

In November 1874, Baldy was jailed under a charge of drunk and disorderly. In November 1876, he was listed among prisoners being released from the Snake Hill Penitentiary. In January 1880, the following piece appeared in the Evening Journal:

Baldy Sours Gone up Again

“Charles Middleton, familiarly known as ‘Baldy Sours,’ in the neighborhood of the Court House, was committed to the County Jail for two months by Justice Aldridge yesterday afternoon. The bleak winds pinched the thinly clad form of the unfortunate old man, and having no home he threw himself upon the mercy of the court, and was provided with winter quarters. He was a self-confessed vagrant, and saw no other chance of getting shelter, and something by which to satisfy the inner man.”

Later that year, a small item in the newspaper reported that he was sentenced to two months in jail for drunkenness. Sometime in the months thereafter, Baldy temporarily pulled himself together and tried to mend his ways but it didn’t last. On August 15, 1882, the Evening Journal reported that “Charles Middleton, known as Baldy Sours, was sent up for 90 days. He is a genial, good-natured man, perfectly harmless to everybody but himself. He had been behaving for more than a year heretofore.”

The cycle of arrest, jail and release continued for the next two decades. At the time of the taking of the 1900 U.S. census, Charles Middleton is found “at home” in the inmate population at the Hudson County Jail. He gave his year of birth as 1828, making him about 72 at the time and indicated he was “single” and born in New York. A year later, in September 1901, the venerable New York Times reported the following:

Dies in Jersey City Jail

“Baldy Sours” Rarely Had Been Out of It for the Last Thirty Years

“Charles Middleton, alias ‘Baldy Sours,’ died yesterday in the Hudson County Jail at Jersey City. He came out of a respectable New York family, who allowed him a monthly stipend. He was seventy-five years old, and for the last thirty years he has not been out of the county jail a month at a time. He called it his home, and he was known as the star boarder because the allowance made by his relatives enabled him to provide his own meals during the greater part of his imprisonment.

A man of more than ordinary ability, drink was his besetting sin. He was never arrested for anything but drunkenness. He was known to every Justice in Jersey City, and whenever he was arraigned he was at once sent to what he called his ‘home.’ On one occasion he was arrested in Hoboken, where he was a stranger, and sentenced to thirty days in the penitentiary. ‘That’s wrong,’ said Middleton. ‘I belong to the county jail. Make it ninety days there instead.’

A county court officer who was present explained matters to Frank McDonough, who was then the Recorder, and the sentence was changed in accordance with Middleton’s suggestion. He was employed in light work about the jail, and one day was sent to trim some flowers in the jail yard. He walked off. The next day he returned. Charles Birdsall, the Warden, refused to admit him.

‘You can’t help yourself,’ said Middleton. ‘I was sentenced to thirty days, and I have only served twenty.’

‘You violated your parole,’ said Birdsall, ‘and I won’t take you in.’

The matter was finally compromised by Middleton’s subscribing to an affidavit that he would never run away again. As the address of his relatives is not known, Middleton’s funeral expenses will be borne by Sheriff Carl Ruempler. ”

Of course, Baldy’s hometown newspaper, the Evening Journal, also reported on his passing. In addition to reporting much of the same story that ran in the New York Times, the Journal piece reported that Baldy had died “at his home” from heart disease and “only had time to say Good bye Joe,” to the night jailer Mr. Tucker. The article went on to say that Baldy was a man of some education and “his money belonged to everyone he met” and that he was first sent to jail about thirty years earlier. He was described as short in stature and having a gray beard and with the skills of a “professional horticulturist.” Among Baldy’s duties around the jail and court house were the care of his “friends” Tom and Jerry, the two alligators who lived in the court house fountain basin. The Journal article concluded by saying that “as a helper around the jail, Baldy was without equal,” and was the Trustee in charge of Ward No. 1 in which all the murderers were kept.

While local law enforcement was ready to pay for Baldy’s funeral, it was not necessary. Charles “Baldy Sours” Middleton’s New York relations heard of his death and his sister came to the morgue to claim his body. He was interred in the Middleton family plot at Cypress Hills Cemetery.

Not long after Baldy’s passing, a short article appeared in the Evening Journal:

Kelly Succeeds “Baldy”

“Since the death of ‘Baldy Sours’ Middleton, the star boarder in the County Jail is William Kelly, who for the past fifteen years has been an intermittent guest of the county. The death of ‘Baldy’ has advanced Kelly to the position of ‘Trustee’ No. 1 and he has charge of Ward No. 1 which for years was under the control of ‘Baldy.’ Kelly has also succeeded ‘Baldy’ as custodian of the Court House fountain.”

Part Two: The Hudson County Jail’s Star Female Boarder, Bridget Coogan

Baldy Sours had a female counterpart at the Hudson County Jail. According to the Evening Journal, the lady, Bridget Coogan, was “the only true friend” of Charles “Baldy” Middleton. Born in Ireland in the early 1830s, it appears that she came to the U.S. in the late 1840s during the Irish Famine. Over the years from the 1860s forward, she frequently made the pages of the Journal, arrested for petty and grand larceny, drunk and disorderly, vagrancy and the like. In 1873, the Journal reported that she was “committed to the workhouse for 60 days for making a beast of herself.” Yikes.

She served most of her sentences, which usually were for 30, 60 or 90 days, in the Hudson County Jail but also spent time as an inmate at the Snake Hill Penitentiary. At the time of the 1880 U.S. census, Bridget was at Snake Hill. The census indicates that she was a married woman, occupation: housekeeper. Apparently, after leaving Snake Hill, she tried getting sober. (I imagine that a sabbatical at Snake Hill in those days was a bit of a “scared straight” experience for someone used to lodging with the jailers at the Hudson County Jail who knew her so well.) Picked up in October 1880, the Journal reported that Bridget, who had been sober for some months, “fell from grace and was gathered in, but was given one more chance.”

In her earlier years as a local criminal, several of Bridget’s escapades made the pages of the Journal. On December 27, 1875, Bridget was arrested on suspicion of larceny. At the time, she was in the employ of a Mrs. White who accused her of stealing a shawl. “On examination, Bridget proved that she had borrowed the shawl and had no intention of stealing it.” The article concluded that Bridget’s bad reputation had led to her arrest. The charges were dropped.

In 1872, Bridget and gal-pal Mary Lowry were picked up and put in the “cage.” Mary, described as having a “long, thin, cadaverous face,” and holding fast to her umbrella and a small parcel wrapped in torn newspaper laid down and went to sleep. Bridget, described as a “stout, strapping, specimen who could with ease take an ordinary-sized man in her arms and spank as well as smack him,” sobered up more quickly and philosophically stated that she “had a damned right to do as she pleased with her loose change, and she’d just enjoy herself whenever she liked – Judge or no Judge, law or no law.” The article went on to comment that it was “a pity a woman so combative and independent should select benzene to tickle her appetite and fire up her brains.”

When called before the Judge, he asked Bridget when she left the workhouse. “Yesterday, sir,” she replied. “You made haste Bridget,” said the Judge. “It’s a bad job, Bridget.” “Yes, sir,” said Bridget. “But who wouldn’t when they’re kept up there for a month or so working for the county?” The arresting officer testified that he had picked Bridget up at 10pm the prior evening at the corner of Washington & Montgomery Streets (Jersey City) as she was quarreling with a group of boys gathered around her. He told the Judge that she turned her “batteries” on him with a barrage of abusive language he had never before heard uttered by a woman. Bridget said nothing until the sympathetic Judge asked her if he let her go this time, would she try to get a job. Brightening, Bridget said she could try. The Judge bade her depart in peace and try to sin no more. The Journal concluded that Bridget’s resolution wouldn’t amount to much as she was “a natural bummer and easy-going (jail) revolver.”

My person favorite was the Evening Journal article of February 28, 1873 titled “Past Experience Unheeded.” Written in a style that was worthy of a poet describing a fair damsel, it went as follows:

“Unheeding the experience of many years, she drank deep numerous potions of an intoxicating and fiery beverage, commonly denominated ‘rum.’ The usual results from an undue attachment to lava followed. The cherub face and sylph-like form of sweet Bridget Coogan sank amid the heaps of beautiful snow, completely overcome; her mind and optics completely oblivious to passing events. Then did a knight of the baton (policeman), with a chivalry like unto that of a different age, raise the angelic Bridget and carry her boldly to the precinct number three. The cadi (court) dealt with her judicially this morning, for, having no lucre (money), she languisheth.”

In late 1876, Bridget had solidified her sketchy reputation when the Journal reported the following:

“Bridget Coogan has been well known at the station houses in this city for years past. Yesterday, Officer Bottner arrested her for being drunk on the street, and this morning a lady who knows Bridget paid her fine for her, took her home and will try to make a decent woman of her, and it is hoped that she may succeed and Bridget be reconstructed.”

Those hopes were for naught. I found no less than two dozen newspaper stories mentioning Bridget’s arrest from the 1860s to the turn of the twentieth century. When the 1895 New Jersey State Census was taken, both Bridget and Charles “Baldy” Middleton were among the inmates of the Hudson County Jail. Five years later, at the time of the taking of the 1900 U.S. census, Bridget, like Charles “Baldy” Middleton, was again residing in the Hudson County Jail. Matter of fact, their names appear on the same census page. Her age was shown as “about 71” and it was indicated that she was a widow and had never had any children.

In September 1901, the Evening Journal ran an article titled “Alone In Cell, She Mourns For Baldy – The Only True Friend the ‘Star Boarder’ of County Jail Ever Had – Their Lives Ran in the Same Channel, and When the Morgue Man Called for ‘Baldy Sours’, She Wept Silently and Alone.”

The article described Bridget as sitting in the women’s ward of the County Jail “with tearful eyes, probably the only sincere mourner for the departed” Baldy Sours Middleton. The piece claimed that Bridget had been a regular at the jail for nearly 50 years and that she and Baldy were single-mindedly “swayed by fondness for drink and their love for the County Jail.” Apparently Bridget began her relationship with the jail before Baldy but they soon came to know each other as fixtures there. The story speculated that although Bridget and Baldy had a long-time friendship, they were never “destined for a warmer sentiment” because their love of liquor was stronger than their caring for each other.

Bridget was fond of dressing herself in “gaudy calico” when discharged from the jail and it was believed that Baldy bought it for her. A day or two later, Bridget would be back, once again arrested. Baldy would greet her and she would tell him that she had a hell of a time while gone. When Baldy was released, the story would be much the same. When Baldy would return, once again arrested, he would bring Bridget two new clay pipes and two pouches of tobacco. When Bridget heard of Baldy’s death, she lit her pipe and sat by the barred window of her cell. It was said that she was heard saying, “Good-bye Baldy, Good-bye,” as the morgue attendant removed Baldy’s body from the jail.

Just eight months after Baldy’s death in the Hudson County Jail, Bridget Coogan also died there. The Evening Journal ran a small piece with a headline in all caps “Bridget Coogan Died This Morning.” On May 7, 1902, the Journal reported Bridget’s burial in Holy Name Cemetery “in consecrated ground.” Bridget’s death was also reported in at least one New York City newspaper and, on May 12, 1902, the Denver (Colorado) Post picked up and ran the following New York Herald article:

“Jail Her Only Home – Queer Octogenarian Slave to Drink Dies in Prison”

The article talked of Bridget’s weakness for the drink and said that jail officials estimated that she had been committed to the jail more than one hundred times. She had “earned a record as a model prisoner early in her career, and inevitably had a place in the squad of ‘trusties’ assigned every afternoon to clean the court-house offices every afternoon. In this way she formed the acquaintance of every county official who held office over the past quarter century. In spite of her many visits to the jail, little was known of Bridget’s history as she never could be induced to talk about her family.”

(Post-Script: I would be remiss if I didn’t tell you what became of the star animal boarders at the jail and courthouse complex. Tom and Jerry, the two alligators taken care of by Baldy Middleton, came to live in the courthouse fountain basin in about 1899-1900. Bridget, Baldy, Tom and Jerry – fixtures at the Hudson County jail. In 1904, a few years after the passing of Baldy and Bridget, tragedy struck again when Jerry, according to the Evening Journal, “in a fit of cannibalistic unfriendliness” killed his buddy Tom, devouring all of Tom except his head and tail. Less than a year later in 1905, the Journal reported that Jerry, suffering a “life of loneliness” simply lay down and died.)

*************************************************************************************************

May 2011

Gangs of Another City

Part One:

Jersey City has always had a connection with New York City, actually, a number of connections. In the early 1800s, when Jersey City was in its infancy, it was a sleepy suburb of its neighbor across the water. Over the ensuing years, some of New York City’s successful businessmen and professionals took up residence in Jersey City, then something of a bedroom community. A short ferry ride provided a means of commuting . . . some things never change. Like its much larger sister-city, Jersey City was also home to the poor and lower classes that generally consisted of European immigrants and native-born Americans drawn to the city by the jobs resulting from growing industrialization.

With population growth, economic struggles and social change came the inevitable crime. New York had its infamous gangs like those depicted in the memorable film, Gangs of New York. Its little sister was no different. In the second half of the nineteenth century, Jersey City was home to many gangs who claimed specific streets and neighborhoods as their turf. These hoodlums and toughs instilled fear among residents and local business owners as they committed robbery, burglary, assault and even murder, making it unsafe to walk the streets, particularly after dark. Those they victimized were often too afraid to testify against them, making it more difficult for law enforcement to arrest, prosecute and incarcerate them. Boys as young as nine or ten years old were often initiated into these gangs, committing crimes alongside young men twice their age . . . and just as often sent out on their own to do the dirty work for the older gang members. Among the Jersey City gangs of the 1880s era were the Red Tigers (whose members reportedly included two brothers of Jersey City’s famous mayor Frank Hague), Glass House Angels, the Trestle Work gang, and the Lava Beds, also known as the Featherstone gang.

The Lava Bed gang operated in the 1880s and 1890s in what was the Sixth Ward, a poor neighborhood characterized by vacant lots, swamp, standing pools of water . . . and rocks, both large formations that the gang used like a fortress and smaller rocks used for makeshift fire pits fueled by burning refuse that left piles of ash behind. This desolate, rocky environment, where waste from a local soap factory was reportedly dumped, only to foam up when it rained, was sometimes called the lava beds, hence the name of the local gang of hoodlums. The Lava Bed boys used the rocks as cover from police and as weapons of assault and vandalism. In the Sixth Ward, as in modern gang neighborhoods today, there was a perverse kind of status that came with being a Lava Bed member and also like today, the Lava Beds had specific initiation requirements for prospective new members that included committing a burglary or robbery single-handedly or “laying out” a policeman (often with a blow to the head using one of those local rocks). The book, History of the Police Department of Jersey City: from the Reign of the Knickerbockers to the Present Day, published in 1891, described the Lava Beds as “a wild, vicious lot, with no homes, no attachments, and without anything whatever to hold them in check except a policeman’s club.” The author, Augustine Costello, went on to say that the Lava Beds, whose territory was near the train tracks, were fond of breaking into freight cars, moving on the rails or sitting in the train yard, and helping themselves to livestock or whatever else they could steal.

The six Featherstone brothers were the heart of the original Lava Bed gang which formed in the mid-1880s, although the brothers had been budding criminals before that and more than one of them had spent time in reform school early on. In prior book research, I had hit upon some newspaper stories about the infamous Featherstone brothers and my curiosity was piqued. I decided to see what I could find out about these very bad boys. Perhaps they were orphans left to fend for themselves and were drawn into the criminal life. With that, the genealogical hunt was on for the notorious Featherstones of Jersey City.

As it turned out, the Featherstone boys were not orphans. Their parents, both born in Ireland, were Michael, born in 1830, and Catherine Ivers Featherstone, born in 1836. The Featherstones’ oldest son, John, was born in Ireland in about 1859. Their five other sons, all born in New Jersey, were James, born in 1862, Michael Jr., born in 1864, Mark, born in 1867, William, born in 1873, and Edward, born in 1874. The Featherstones also had one daughter, Julia, born in New Jersey in 1866. With the birth of their first son John having occurred in Ireland in 1859, and the birth of their second child having been in New Jersey in 1862, we can surmise that the Featherstones married in Ireland and emigrated to America between 1859 and early 1862 with their young son John. Michael and Catherine Featherstone were survivors of the Great Famine in their homeland and arrived in New Jersey during our Civil War. They took rooms in Jersey City and lived for many years in the 400-block of First Street.

That location (the 400-block of First Street) rang a bell with me. It didn’t take long for me to figure out why. My own Irish-born great-great-grandparents, Patrick and Catherine (Jordan) Whalen lived at 400 First Street at the time of the 1880 U.S. census. Also living at that address were my great-great-grandmother Catherine’s two brothers (James and Patrick Jordan) and their families. At that same time, the Featherstones and their seven children were living at 420 First Street. My great-great-grandparents were recorded on page 365 of the census ledger; the Featherstones on page 366. Their rooms were just a few buildings apart on the same side of the street. It immediately occurred to me that my Whalens must have known the Featherstones. Very quickly, though, two other realizations came to mind: my great-great-grandparents lived in that awful, desolate, poverty-ridden neighborhood I described earlier . . . and they were no doubt among the residents frightened, intimidated and victimized by the Featherstone boys and their Lava Bed gang!

Part Two: Gangs – A training school for criminals

In 1880, the census-taker made his way down First Street, interviewing and gathering statistics on each family, most of them, including the Featherstones, headed by Irish immigrants. The Featherstones were recorded as a family of nine. Michael Featherstone Sr. was listed as an Irish-born laborer and his wife as “keeping house”. Oldest son John was also listed as an Irish-born laborer. Julia and Mark (sometimes called “Marx”) were age 14 and 13 and were listed as “at school”, meaning they were attending elementary school. William and Edward, ages 7 and 6, were not yet attending school. Sons James, 18, and Michael Jr., 16, were in a very different kind of school. The census listed them as “in Reform School”. In fact, James and Michael appear in the 1880 census twice: once under their parents’ address at 420 First Street in Jersey City and a second time as inmates of the Jamesburg Reform School in central New Jersey.

Seven years before the census-taker’s visit, in August 1873, the Evening Journal newspaper reported on a melee that broke out on First Street, specifically, in and around 420 First Street. The article, titled “A Donnybrook Fight on First Street”, was subtitled “Scalps as Thick as a Hudson River Fog”. (You’ve got to love those colorful, entertaining nineteenth century newspapers. They really knew how to hook the reader and fill a column of print space.) The best way to tell you what happened on First Street that Saturday night is to let the Evening Journal tell the tale as originally told in its pages nearly 140 years ago:

“First Street, formerly South Eighth Street, near the Point of Rocks, has always been a spot in our city where a man could get his eye blacked or his skull cracked quicker and easier than he could at any other portion of Jersey City. Here Connaughts, Fardowns, Tipperarys, Corkonians, Galwayians and Dublinites (all terms describing Irish by the county in Ireland from which they came) live not in peace and harmony, but in eternal warfare, each section ready to meet the other in a friendly set-to, or ready, at the slightest hint, to “tear the coat off” the spalpeen that comes from any other county than that from which the challenger first drew his breath. On Saturday night last, in that populous section near 420 First Street, the passers-by could hear loud and angry words coming from the different windows, each hallooing at the other, and using phrases that would disgust the worst denizens of Baxter Street, New York. About 11 o’clock the war broke out, and Michael Shanley and his son James Shanley, came out of their holes in a right-good humor for a grand fight. James Shanley fell upon Patrick Higgins with a slungshot or club, and made short work of him, leaving wounds thus described by Dr. Oscar T. Sherman: “A contusion and lacerated wound on right side of the head, above the temple, with a suffusion, and liable to result fatally”. Michael Shanley fell upon a man named Michael Featherstone (Sr.), and ‘ere he got through with him, left him in a condition which is thus described by Dr. Sherman: “Two contused and lacerated wounds on the head, situated on the right and posterium part of the head, about three and a half inches in length, above the ear; a cut about two inches in length with more or less suffusion under the skin, and other wounds less in extent, situated on the left side of the head, in the same relative position as the others, all of which wounds may prove fatal to the sufferer”. Justice Fred Payne was sent for yesterday afternoon and took the affidavit of Featherstone at his bedside, against Michael Shanley, whom he charges with a murderous assault, and the culprit was arrested. Mrs. Catherine Featherstone, then appeared before Justice Ryan and made an affidavit that Michael Shanley and his wife Mary made an assault upon her, at the same time and place, with a bayonet, cutting her hand and otherwise injuring her bodily. Both of these parties were arrested by special constable Sumers and gave bonds of $500 each, ex-Alderman John Lennon becoming their bondsman.”

Just three weeks later, on September 9, 1873, Michael Featherstone Sr. made the Evening Journal again, proving that, however serious, his injuries in the melee were not fatal. This time the article was titled “Struck by the Cars” and it was more bad news about Mr. Featherstone. At about 6:30 one evening, Featherstone was struck by a Pennsylvania Railroad train as he was walking on the tracks near Monmouth Street. According to the newspaper, “the unfortunate man’s legs were horribly mangled and his head badly injured. He was picked up by Officer William Kelly, who, with assistance, carried him home to First Street. Dr. O’Callahan attended him, but he has no hopes of his recovery”. (Believe it or not, he did survive and lived another twenty-four years. Perhaps either the beating by his neighbor or the train accident left him disabled but, whether he was or was not, he did not pass away until 1897 at the age of sixty-seven.)

In May, 1874, about eight months after Michael Featherstone was hit by the train, his namesake, Michael Jr., made the pages of the Evening Journal. He was about 4 months shy of his tenth birthday. There had been a theft of a large quantity of lead pipe from the Brunswick Street home of a Terence Beggins. The police first arrested James Fullerton for stealing the pipe and a junk dealer, John Lynch, for buying it from the thief. Shortly after those arrests, Edward Kelly and young Michael Featherstone were arrested for “complicity in the robbery”. The article stated that Kelly and Featherstone belonged to a gang that had recently taken up quarters in a furnished house on Mercer Street that was temporarily vacant as the owners were away and indicated that more arrests in the case were expected. Nine-year-old Michael Featherstone Jr. was on the road that would lead to his incarceration at the Jamesburg Reform School about five years later. In September 1874, the Evening Journal reported that young Michael Featherstone had been “committed” on a charge of larceny. Two years later, in 1876, an Evening Journal article recapping court proceedings included a line about the arraignment of a “boy”, James Featherstone, who pleaded guilty to a charge of robbery and was held for sentencing. James was thirteen at the time of the arraignment. It is likely that older brother John Featherstone, who would have been about 15 at the time, was an up-and-comer in the gang and sponsored younger brothers James and Michael’s initiation into the group.

Big brother John himself made the pages of the Evening Journal in January 1878 at the age of seventeen in an article titled “A Young Blackguard Punished”. Featherstone had accosted a young couple named Jones, blocking their path on the sidewalk and then addressing an “obscene remark” to Mrs. Jones. Mr. Jones knocked Featherstone to the ground and a beat cop, Officer Conway, picked Featherstone up and took him in. While in custody, it was discovered that Featherstone was wanted under an active warrant for smashing the windows of a saloon on First Street (near his home). The proprietor of the saloon, Mr. Miller, had refused to supply Featherstone and “his crowd” with free rum so they vandalized the saloon. John Featherstone was “sent up” for 90 days for insulting Mrs. Jones to be followed by another term for the saloon incident.

While Michael Jr. and James were cutting their criminal teeth in the mid-1870s under the tutelage of their older brother John, their mother Catherine was giving birth to the youngest Featherstone boys, Edward in about 1872 and William in about 1874, while caring for their young sister Julia and little brother Mark, then about six or seven years old. The Featherstones were Catholics and were parishioners of St. Mary’s R.C. Church where their children were baptized. Catherine Featherstone lost at least one child, Annie, in 1866, and likely lost another named Thomas in 1878.

In 1881, the Evening Journal reported a raid on the Lava Bed gang on First Street. The article told of the need for frequent raids to keep the gang of thieves and “loafers” under the “subjection” of the police, those raids happening at the direction of Captain Farrier. Picked up in the midnight raid were six young men including Michael Featherstone, each of whom was given the choice of paying a fine of $20 or being locked up for 90 days. Just after that raid, young William Featherstone was arrested at the tender age of seven, charged with burglary committed at Lahey’s grocery store. While these offenses may seem hardly worthy of police raids, the Lava Beds and other gangs in Jersey City routinely victimized residents and business owners on a daily basis, making the streets unsafe. Mothers were afraid to let their children play outside for fear of violence or their young boys being recruited by gang members. Women and young girls were accosted on the street and became victim to lewd remarks and even sexual overtures and assaults by these brazen gang members, making it unsafe to go out alone even in the daytime hours.

Part Three: She died of a broken heart

The Lava Bed Gang, we’ll call them “LBG” for short, made the pages of the Jersey City’s Evening Journal and the New York City papers as well during the 1880s and 1890s. In August 1882, the Journal reported the following starting with the subtitle “A Nest of Hoodlums Broken Up – Lively Encounter”:

“First Street abuts upon the rocks at its western extremity, and in that neighborhood has long existed a gang of hoodlums known as the ‘Lava Bed Gang.’ No sort of property is safe from these fellows. Portable property is seized and carried off almost with impunity. A protest from a victim is visited with outrage and carnage by the gang. Real estate is broken and defaced and tenants are driven out by the conduct of the hoodlums. Mr. Wm. Howeth, who owns houses in the neighborhood, has been a sufferer for years. He succeeded in sending a few of the gang away, and their loss is a gain to the neighborhood. Last Saturday night, the owner of 420 First Street complained to Capt. Farrier that a gang of hoodlums had taken possession of the upper floor of his house and refused to leave. They had made it a headquarters, whence they sallied forth to steal and to which they returned their booty. Capt. Farrier waited patiently until 4 o’clock yesterday when he called several officers in and organized a raiding party. The house was surrounded. In the hallway were found four hoodlums who were placed under arrest and left with a guard while a squad ascended to the top floor where four more were taken. While they were being searched there was a lively time in the hallway. Officer Stucky’s prisoner knocked him down and made an attempt to escape. Officers Graves and Whelan were tripped going to Stucky’s assistance and a prisoner ran. A pistol shot raised the skin on the fugitive’s arm and he stopped. By this time, the neighborhood was aroused and the officers hastened away with the prisoners. Nearly all of them are notorious characters. They gave their names as John Ryan, John “Red” Doyle, Edward Harris, Walter McCue, Edward Hayslip, Fred Harrion, John Featherstone and James Featherstone. All but Ryan and Harris were convicted by Judge Stilsing who sent the six away for 90 days each. Hayslip is wanted for the assault upon Mr. and Mrs. Evans, which caused the latter to give premature birth to a child and nearly caused her death. The Featherstones are a bad crowd. Another brother was committed for robbery this morning. This wholesome dose of correction will thin out that gang for some time, and is therefore a blessing to the public.”

The New York Herald reported the same event under the provocative headline: “HINT TO THE NEW YORK POLICE:”

“A band of Jersey City ruffians and thieves, known as the “Lava Bed Gang,” were raided yesterday by a squad of police, under command of Captain Farrier, and eight of the lawless ruffians composing it were captured. The band was broken up some time ago and several of the delectable coteries were sent to prison. Recently, some of those who had been released were noticed loitering about their old haunts at the head of First Street, and, as reports of petty thefts and assaults were becoming frequent, the police were convinced it had reorganized and had a rendezvous near the rocks. Three of the band were fugitives from justice, but it was decided not to interfere with them until their hiding place was discovered. On Saturday, it was ascertained that they had taken possession of two rooms on the top floor of the tenement, No. 422 First Street. The band is composed of desperadoes, and anticipating a stubborn resistance, Captain Farrier summoned his entire force of night men and at four o’clock yesterday morning started for the nest. They approached the place quietly, burst in the door and surprised and caught the band, the majority of whom were asleep. They were not disposed to submit quietly, but the policemen subdued the leaders, who made a show of resistance, and the eight prisoners were taken to the Gregory Street station and locked up. Those captured were John Ryan, Edward Harris, Frank Dougherty alias Red Doyle, Frederic Harmon, Morgan McHugh, Edward Hyslip (Hayslip), John Fetherston (Featherstone), and James Fetherston (Featherstone). Hyslip will have to answer for committing an atrocious assault on a Mrs. Evans, who was so brutally beaten that her life was for a time despaired of. John Fetherston is wanted for robbery and cruelly beating a little girl and his brother James for burglary. The prisoners have, with one or two exceptions, been in jail. Their ages vary from seventeen to twenty-eight years.”

While his brothers John and James were away serving that 90-day sentence, Michael Featherstone kept the home-fires burning in partnership with the same Edward Hayslip . The Journal, under the title “Only Another Crime,” reported that Mrs. Marly’s “fancy store,” No. 356 First Street, was broken into and $20 worth of socks had been stolen. Captain Farrier, who already had Michael and Hayslip in custody, went to their cells only to find “some of the stolen property on the feet of Michael Featherstone and Edward Hayslip.”

In January 1883, the Journal, in reporting activity at the county courts, reported on the trial of John Featherstone and an accomplice, both identified as members of the LBG. (Featherstone would barely have been past the 90-day sentence above when he was back in police custody again.) More than telling the facts of the trial, the short piece gave a chilling criminal bio of John Featherstone. Featherstone was on trial for breaking and entering with the intent to commit assault and battery and had a court-appointed defense attorney named Samuel McGill. On December 6th, the complainant Mr. William Kerr had sent his “little girl” on an errand. She was accosted by Featherstone and friend and “abused.” Mr. Kerr came to his daughter’s aid and told the two assailants to clear the passageway to his home. Instead, the hoodlums chased him up the stairs and broke down his door. Mr. Kerr said that one of the defendants said “Hit him with a brick.” John Featherstone denied being there and said it was one of his brothers, not him. Mr. Kerr’s neighbors corroborated his version. Featherstone admitted having once been in State Prison for 18 months for assault and battery, and that he had been fined and imprisoned at Snake Hill a number of times for various offenses. He “hypocritically said that he had been trying to make a man of himself” to which the prosecutor responded by stating the obvious – that he had not succeeded. The jury shortly brought in a verdict of guilty against both Featherstone and his accomplice.

So, what can we conclude thus far about the LBG? They were young men who operated in their own backyard . . . literally . . . preying on and brutalizing their “own kind,” ethnically and economically. Utterly without a moral compass or conscience, they passed the time and amused themselves by stealing socks one minute and beating a pregnant woman nearly to death the next. Sound familiar – people seeing life as cheap? Some things never change.

The New York Herald continued to follow the exploits of the LBG and in April, 1883, ran a story titled “Going Back to the Farm.” The article told the story of James Smith and his wife who had lived “happily” on a Connecticut farm for many years but could not make progress in “accumulating a fortune” and so decided to sell that farm and open a business in the city. Having a cousin in Jersey City, they set up a small grocery store with liquors there, rents being cheap. Unfortunately, their choice of location, the upper end of First Street, was the territory of the Lava Bed Gang, “a crowd of young thieves, several of whom are now rendering the State service.” Describing the LBG as “the worst in Jersey City,” the article went on to say the gang had been led by John Featherstone or one of his two eldest brothers, depending on which of them was not in the State Prison. Gang members were the first “customers” to come into James Smith’s newly-opened store. They sampled the liquors and opened “accounts.” They kept returning to “sample” the liquors until the “old farmer-merchant” objected and asked for payment for open accounts. A gang member threatened to “wipe out the place” and left. Minutes later, a chunk of concrete pavement came flying through the front glass window of the store, almost striking Mr. Smith. John Featherstone and his gang then entered the store, wrecking the place and causing the aged couple to flee. The Smiths told Judge Stilsing what had happened at the store and Featherstone was arrested and committed for trial. As he prepared to leave the courtroom, Mr. Smith said to Judge Stilsing, “I guess my wife and I will go back to farming. I will give you my address in Connecticut. Please notify me when the trial is to take place and I’ll be here.”

The Journal also reported that, upon John Featherstone’s arrest, others came forward to report recent crimes committed against them by John Featherstone including a woman who said he had assaulted her.

The revolving door of justice apparently kept spinning and the Featherstone boys rode it like a carousel, moving in and out of the judicial and prison systems time and time again, month by month, year after year. They no sooner were released than were back at it again – thieving, breaking and entering, assaulting, vandalizing, extorting businesses and the like.

It was no different the next year, 1884, when the Journal reported that the LBG who “infested” the Sixth Ward, “made a raid” on the saloon of Adam Metzger on Railroad Avenue near Brunswick Street. When refused free liquor, they began to wreck the saloon, breaking windows and doors. The same year, the New York Herald reported that the LBG, “a notorious band of Jersey City hoodlums,” had a post-prison-release “reunion,” the majority of them having just been released after three months in State Prison. The celebration was timed to include one member, John Darcy, who had been “away” for two years. The partying started just before midnight with a raid on a grocery establishment where they procured free drinks and then each “appropriated a new broom.” They then prowled about in the old Sixth Ward and “besieged saloons and dwellings,” using the brooms on those they encountered as persuasion to provide free drinks. If refused, they destroyed the place. Two police sergeants and an officer came up upon the gang on First Street. The alarm was sounded and the gang scattered but the police did capture three of the hoodlums: William Hanley, John Darcy and John, alias “Pucksie,” Featherstone.

It was also in 1884 that something more personal happened in the lives of the Featherstone boys. In May of that year, Catherine Ivers Featherstone, their mother, passed away. She was 48 years old. In his 1891 book, History of the Police Department of Jersey City, Augustine Costello, in describing the LBG as “the wickedest gang in Jersey City,” wrote the following:

“The Featherstone parents and one sister, Julia, were very respectable folks, as respectability goes thereabouts, and the mother died of a broken heart it is said, grieving over her sons’ misdeeds.”

Part Four: The Beat Goes On……

Truth be told, the cause of Catherine Featherstone’s death was “Phthisis Pulmonalis”, better known as tuberculosis or consumption, a disease that was the scourge of 19th and early 20th century cities in the United States. She was buried in Holy Name Cemetery, joining two sons she lost in early childhood.

Perhaps it was a mercy that Catherine Featherstone was not alive to see the waning days of the 1800s as, despite the passing of time and defying any expectation that they would outgrow their youthful deviant behavior, her “boys” got older all right . . . but no better. The Journal and New York newspapers continued to tell the tale of the LBG, the Featherstones and their gang brethren which included three one-legged warriors named Fisher, McGee and Sherry, each of whom had reportedly lost a leg due to being run over by railroad cars while committing robbery.

In 1885, Michael Featherstone, then living on Third Street, was arrested for “raiding” the apartment of one Terence Brady, a tailor, who lived in the same building, and robbing a “suit of clothes” valued at $40. Suspecting his neighbor Featherstone, Brady sought him out and found him coming out of a local pawn shop. Featherstone had just pawned the stolen suit, getting $2.50 for his efforts. The New York Herald picked up the story and amplified on it. The Herald identified Michael Featherstone, age 20, as one of the Featherstone brothers, “four desperate young fellows,” all leaders of the LBG of Jersey City, the “most persistent and notorious gang of law breakers that the Jersey City police have to deal with.” The article went on to say that although half the gang was then in State Prison for crimes including highway robbery and burglary, “they manage, however, to recruit their ranks and fill the places made vacant by the retirement of the veterans to prison.” Among those then in prison were two of the Featherstone brothers including John Featherstone who, according to the Evening Journal, had broken into five grocery stores in one night.

By April, 1886, when the Journal ran a piece titled “The Lava Bed Gang Again”, it reported that only one of the “Featherstone boys” was not in prison. By September, 28-year-old John Featherstone, once again out of prison after serving a State Prison term for burglary, was back in custody after beating a man on the corner of Monmouth Street and Railroad Avenue because the man refused the LBG’s demand for money for beer. The same month, his brother James, also just out of prison, was held on a charge of larceny. Not to be outdone, younger brother Mark (sometimes known as “Max”) was picked up a few weeks later after a foot-chase by Jersey City police on a charge of being a disorderly person.

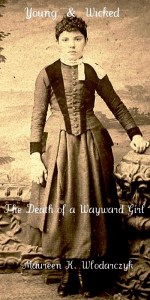

Max, who was the youngest of the four notorious brothers, was beginning to make a name for himself. In March, 1887, his offenses escalated. The Evening Journal reported, under the title “Frightful Outrage,” the assault on a woman in her own home by five men. “Outrage” meant sexual assault in those days. The victim was a 45-year-old widow, Mary Quirk, who lived alone in the upper floor of a tenement on First Street, near Colgate, right in the heart of Featherstone and LBG territory. Mrs. Quirk reported that, at about 9 o’clock, the men forced their way into her apartment and assaulted her, muffling her attempts to scream for help. She was beaten and held for four hours before escaping. Mrs. Quirk recognized Featherstone and one of the other men from the neighborhood and courageously named and identified them for the police.

John, James, Michael and Max Featherstone, then ranging in age from about 20 to 28 years old, had been terrorizing the Sixth Ward and the First Street neighborhood for the better part of a decade and reportedly had no “home”, just drifting around the neighborhood. Their mother was dead, and their father, perhaps an invalid, may have been trying to care for their sister Julia and youngest brothers William and Edward.

Young William and Edward made the pages of the Evening Journal the following year, in February 1888 at ages of about 14 or 15. The article was titled “Little Outlaws” and it takes us back to Snake Hill. Edward, William and two friends, George Campbell and Charles Enness, were convicted of stealing county property and were sent to Reform School (most likely in Jamesburg, where their older brothers had spent time nearly a decade earlier). William and Edward, identified in the piece as relatives of the “notorious Max Featherstone,” had been “inmates of the almshouse” (poorhouse) at Snake Hill. This implies they were destitute and perhaps homeless and were sent there to live. The article goes on:

“Tiring of the discipline of the institution, they (William & Edward) sought refuge in the woods near Snake Hill. When Robert Ryan assumed charge of the Almshouse, he found the names of the boys upon the register, but learned they had not been in the institution for months before. Upon investigation, he was put in possession of information that led him to believe that the Featherstones and other missing inmates of the Almshouse had established themselves within convenient distance of Snake Hill and made predatory visits to all the county institutions and the neighboring farmhouses, for food, clothing and other supplies. He also had reason to believe that the older boys in the Almshouse were in the habit of visiting the quarters of the Featherstones. He maintained a strict watch, and his vigilance was rewarded by seeing George Campbell and Charles Enniss carrying food to the young outlaws. He followed them and bagged them and the Featherstones. In the home the boys had made for themselves in the woods were found blankets, bed ticking and other property which had been stolen from the Almshouse. Judge Lippincott, in sending them to the Reform School, said it was the proper place for such boys who only demoralize their companions in such a place as the Almshouse.”

And so the criminal careers of the last two Featherstone brothers seemed destined to follow those of their four older brothers.

In the succeeding years, the headlines kept coming, even as the four oldest Featherstones passed through their twenties and into their thirties:

1889: “A Bad Lot” – James Featherstone arrested for bringing “disreputable women” into the neighborhood, placing them in the hallways of residential buildings to facilitate robberies.

1890: “Those Featherstones Again” – John “Pupsie” Featherstone committed for trial for the beating of an old German saloon owner and his wife for refusing free drinks at their establishment on the corner of Newark Avenue and Brunswick Street.

1890: James Featherstone convicted of assault and battery and sentenced to six months at Snake Hill.

1891: “Two Toughs Committed” – Michael Featherstone arrested for the “waylay” and assault on Patrick O’Brien of 418 Third Street, who refused the LBG money for beer.

1893: “The Burglar Identified” – Mark Featherstone, age 28 and a Lava Bed Gang member, of 91 Colgate Street, arrested for attempted robbery at the 430 Second Street residence of contractor John Nolan. Caught by Nolan’s son hiding under a bed in the home, Featherstone made “desperate resistance” and had to be “clubbed.”

1893: “A Beggar Held Up” – Beggar Joseph Harding, refused to turn over his money, 35 cents, and was choked by one man while a second rifled his pockets. Among the three arrested for the robbery was Michael Featherstone of 301 Railroad Avenue. Featherstone, a “leading spirit” in the notorious Lava Bed Gang had just been released following a multi-year prison term.

1895: “Ran Away Under Fire” – John Featherstone of 301 Railroad Avenue and William Stone, no home, were charged with attempted burglary at Sheridan’s shoe store at 473 Newark Avenue. Policeman Lynch fired a shot at the men as they attempted to flee but neither was hit.

1895: “Lava Bed Gang” – First and Second precinct police made a round-up of some members of the “old and notorious” Lava Bed Gang which had been a terror to the city. Chief Murphy and his men have succeeded in breaking up the gang and sent members to prison. Some reformed, some left the city, and those who persisted in being “tough and troublesome” were sent again to prison. Among those picked up in this round-up was John Featherstone, age 32, an “old member” of the gang.

1896: “Lava Bed Gang Returns – Time in State Prison has expired and they resume operations” – “During the past few months several members of the notorious Lava Bed Gang have completed their terms in State Prison and returned to their haunts at the foot of the hill, much to the disgust of the law-abiding citizens in that locality.” Following an attempted break-in on Third Street, police made a raid on several Lava Bed toughs picking up 5 men including Michael Featherstone, alias “Liver,” of 301 Railroad Avenue.

1896: “County Courts” – The Sessions Courts were well-attended as sentences were passed including the following: John Featherstone, resisting an officer and assault and battery – eighteen months in State Prison; James Featherstone, larceny and receiving (stolen goods) – one year in the County Penitentiary;

1897: “Robbed a Restaurant Keeper” – James Featherstone and two cohorts went into a restaurant owned by Mrs. Newhoff, a near-sighted woman. Featherstone flim-flammed her out of $8 by claiming a $2 bill was a $10 bill and his accomplice then snatched the $2 bill from her. Featherstone was given a term of six months by Justice Nevin.

1898: “Charged with Robbery” – James Featherstone, an “old offender and leader of the Lava Bed Gang,” is again lodged in jail, charged with larceny from the person of a 19-year-old Wayne Street man who he dragged into the hall of a house, stealing his watch and some change.

1898: “Four Old Offenders” – James Featherstone and three other old members of the old Lava Bed Gang were arrested for “disturbing the Italian colony” by raiding and theft at a junk store. They were given six months by Justice Nevin to which Featherstone replied to the judge: “Why don’t you hang us?”

On July 6, 1899, Michael Featherstone enlisted in the US Army (perhaps to avoid jail). He lasted all of 40 days and was dishonorably discharged on August 15, 1899 at the Presidio in San Francisco. Perhaps he got into trouble or perhaps they discovered he was a serial convicted felon. Despite the onset of middle-age, James Featherstone kept at it. In 1903, at the age of about 40, he was arrested for grand larceny for stealing twelve dozen napkins embroidered with the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR) monogram and selling them. The police recovered eight dozen of them. As late as 1907, the oldest of the Featherstone brothers, in their late forties, were still making the Evening Journal, arrested for thieving and fencing goods.

If there is any good news, it is that I found no further newspaper articles indicating that the youngest Featherstone boys, William and Edward, had joined up with their older brothers in a life of crime. Perhaps the stint in the Reform School, resulting from their entrepreneurial activities at the Almshouse, proved the deterrent it was intended to be.

Part Five (Conclusion): Miss Julia Featherstone

Catherine and Michael Featherstone were the parents of seven children who survived childhood – six sons and one daughter, Julia Featherstone. They also lost three other children including two sons, one at 6 years old in 1867 and another at 2 months old in 1878. Julia Featherstone was born in August, 1866 in Jersey City and baptized four days later at St. Mary RC Church. Julia was, in fact, a twin. Her twin sister, named Annie and baptized with Julia at St. Mary’s, died just two months later. Julia was named for her Irish maternal grandmother, Julia Ivers (sometimes spelled “Evers”).

At the time of her mother’s death in May, 1884, Julia was approaching her 18th birthday. The following year (1885), the Featherstones were still living at 148 Merseles Street where Catherine Featherstone had died. The city directory for that year lists Michael Sr., James, John and Michael Jr. at the Merseles Street address. By 1891, Julia Featherstone herself, then 25, was listed in the city directory for Jersey City which gave her address as 60 Colgate Street and her occupation as “tobacco worker”, no doubt in the Lorillard Tobacco Factory.

Two years later, Julia Featherstone Trudell gave birth to her first child, Charles Trudell, named for his father. Julia’s husband, Charles Trudell Jr., was no stranger to the notorious Featherstone boys and had his own checkered past. He was born in 1862 in Canada to French Canadian parents, Charles and Harriet Trudell. The family immigrated to the US a few years later and, at the time of the 1880 US census, was living on Brunswick Street in Downtown Jersey City. That census indicates that Charles Trudell Sr. was a carpenter, born in Canada in about 1832. The family included Mrs. Trudell, sons Frederick and David, and daughters Sarah, Kate and Josephine. Charles Jr., the oldest child, then about 18 years old, was listed on the census as “prisoner.” The 1880 census included a separate schedule tracking the homeless, disabled and “inhabitants in prison.” Sheet 18 for Hudson County reveals an early Trudell/Featherstone connection: it listed James Featherstone and Michael Featherstone as “inmates” in Reform School, followed on the next line by Charles Trudell Jr., prisoner in the Hudson County Jail for assault.

Like his future Featherstone brothers-in-law, Charles made the local papers in the 1880s. In October, 1882, the Evening Journal ran a piece titled “Three Terrors in Limbo.” The article opened with the following: “Among the worst and most dangerous hoodlums in the old Sixth Ward are Charles Trudell, Michael Murphy and Otto Kief. These young men are a terror to the neighborhood.” It went on to describe the trio’s robberies and assaults on those who resisted. The specific incident in the article was a theft from a storekeeper named Einstein who did business at the corner of Railroad Avenue and Monmouth Street and had been “beaten almost to insensibility” by the trio because he tried to prevent the pillaging of his store. The three had beaten a man named Thomas Regan the prior night, leaving him “bruised and temporarily maimed.” All three were arrested by First Precinct police. In September, 1884, Trudell pleaded guilty to resisting an officer and assault and battery.